Boathouses of different types are still common along the Norwegian coast from Vest-Agder in the south to

Why are there no boathouses in South east

The reasons for the absence of boathouses in South east

Another fundamental cause for the diverging sheltering practices seems to be the difference between the type of boats used in Western and

To the east of

The eastern, oak-built boats are somewhat more robust than their western conifer counterparts, and this fact may be of some significance for the unequal distribution of buildings used for the protection of boats. Also, the greater weight alone might have done it less appealing to haul the vessels ashore on a regular basis.

Furthermore, the salty winds will do more damage to the iron nails commonly used in western boats than to the tree nails used in the southeastern area (Westerdahl 1989:249)..

Western and

From the above, the reasons for sheltering vessels on the Western coast should be clear. The effects of the spring drought, the rain and the wind on boats being stored ashore made special buildings or roof constructions a neccessity to protect the vessels. While there are some examples in Scandinavia of boat houses being used only in the summer (Rolfsen 1974:12), the vessels in question are relatively small boats that could just as well be brought ashore and turned upside down (Westerdahl 1989:249). During summer it might be enough to leave the boats on water. But this was usually no option at the open, western coast.

The long western coast of

Types of nausts

Traditional boathouses in

Stone nausts:

In Jæren, parts of Lista and the western outer coast stone nausts are a characteristic feature. These have dry stone walls. A wooden frame on top of the stone walls supports the wooden roof. The stone nausts are often dug partly into the ground for stability, depending on the type of stone used. Where flagstones are used, one get very stable walls, and thus it is not neccessary to dig the walls into the ground. This was the case for instance in Hardanger.

Framework nausts:

There are two basic types of wooden boat houses. Framework (‘grindverk’) nausts have wooden, roof-bearing posts joined two and two into frames with with horizontal beams. Framework nausts are, together with stone nausts, the most common type of boat house in

The framework construction have ancient roots. An identical or similar building technique must be presumed for the pattern of pairwise post holes found in prehistoric boathouses like the ones from Nordbø/Rennesøy and Stend. Traditional framework nausts do not have dug-down posts, however. Instead, the posts are positioned directly on the ground or on stone bases.

Somewhat similar to the ‘grindverk’ nausts are the ones constructed in ‘stavline’ construction, the difference being that the horizontal beams in the latter runs along both long walls of the building. Thus, the posts do not make pairs (‘grinder’), and may in fact stand at irregular intervals. Nausts with different variants of ‘stavline’ construction are found from Møre og Romsdal and further north.

In the far North, Saami nausts (‘naustgammer’) are constructed in a technique rather similar to the cruck construction found in a number of traditional barns in the

Log nausts:

Log nausts constructed with horizontal timbers using cog joints are primarily found in Møre and further north, but also in some inner fjord districts further south. Judging from the available material, the lafting technique seems to be an Eastern loan to

Other types of boathouses

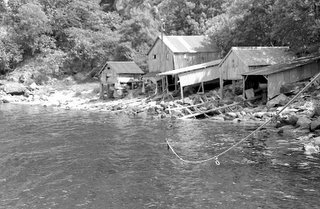

Nausts can be combined with a number of other functions. Buildings combining naust functions with storage facilities for fishing equipment etc (‘sjøbu’) are rather common, for instance in Hardanger, while combinations of naust and sleeping facilities for fishermen (‘rorbu’) are found many places in Western Norway.

Especially in the southernmost part of

This type of boathouse now have a rather widespread distribution, but this is a very modern development, and one linked to the expansion in the use of boats for leisure since the 1930s (Molaug 1985). One core area for these boathouses seems to be the Feda fjord in Vest-Agder, where they seemingly goes back to at least the 17th century. A similar solution to the sheltering problem is found in parts of

In the Feda fjord the boathouses in several cases had a hook fastened to the ceiling, so that the boats could be lifted up in case of bad weather.

The naust rows

At many places in Western and

The first has to do with the limited supply of proper harbour sites. In Spangereid in Vest-Agder, of the 50 or so multi-occupant farms only one did not have access to a beach or harbour – although many farms did not border on the sea. This meant that the nausts or storage buildings of several farms often were located in one and the same harbour. This phenomenon was widespread in many parts of

The forms of landownership in

Ingen kommentarer:

Legg inn en kommentar